By Turaki Hassan

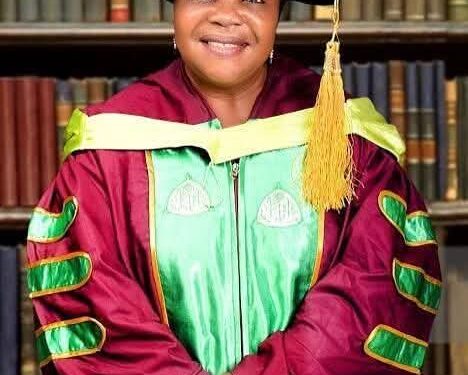

I first met Professor Ladi Sandra Adamu Pankshin physically in 2007, when I was admitted as one of the pioneer students of the Postgraduate Programme of the Mass Communication Department, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. Long before this encounter, her name had already become a household one in Nigerian journalism. Every student or teacher of Mass Communication in Nigeria must have encountered her either personally or through her works—from her days at NTA Jos to her leadership as Editor of the now-rested Democrat Newspaper in the 1990s.

Among her former students, she was known as a tough, uncompromising lecturer—firm, honest, disciplined, and a stickler for rules. She hated laziness with passion. Many would say that “the fear of Madam Ladi was the beginning of wisdom.”

I vividly recall one incident in 2008: I had barely stepped out of my car after arriving from Abuja on a Friday when she asked me to help supervise an assessment test in a very large hall. The strict manner in which I conducted the test left students whispering among themselves—“Where is he from?” “Why is he this strict?” I laughed to myself, thinking that if I had been their lecturer, perhaps they would have reserved an even stronger name for Madam Ladi, since they considered me stricter than her.

One thing was certain: Prof never hated anyone. She simply loved hard work, dedication, and excellence.

She often spoke passionately about her father, the legendary Adamu Pankshin—the first Nigerian to become Regimental Sergeant Major of the Nigerian Army Corps of Engineers—and whose biography she authored, Adamu Pankshin: A Soldier’s Soldier. She delighted in sharing stories of his military exploits.

Towards the end of my studies, she was assigned as my Minor Supervisor, with Professor Emeritus Suleiman Salau as my Major Supervisor. Many colleagues sympathised with me, believing her supervision would be “tough.” Ironically, I became one of the few who finished my thesis early—completed, defended, and graduated. Even Professor Salau had little work left to do, because she had diligently and dutifully guided me through the entire process. She would proudly tell anyone who knew me that I was the best student in the pioneer set, and she tried to persuade me to join the department as a lecturer.

Our relationship blossomed beyond teacher and student—it grew into one of mentor and mentee. She would call to ask for project topics for her students, share her research papers and articles, and update me on her participation in major international conferences in journalism and broadcasting, which she often sponsored by herself.

By divine providence, I later found myself connected more deeply to her family, where she spoke passionately and positively about me. At times I would receive calls from her students, saying she had given them my number to assist with one task or another.

I often wondered why she loved, supported, and guided me so sincerely. Though we had not communicated for a while, on September 16 I sent her a WhatsApp message informing her that I had successfully defended my Ph.D. thesis. She responded joyfully: “CONGRATULATIONS. I wish you the best in your career.” It was unusual that she did not call, but I simply assumed she was busy—not knowing she was already lying on her sick bed at that very moment.

Sadly, that was the last time we communicated. She did not mention her illness, and I had no idea she was in pain. Such is life—people often suffer silently while we assume all is well. Even while unwell, Prof continued posting messages of condolence and celebration on Facebook. When we were bereaved last year, she drove from Zaria to console us despite telling me she wasn’t feeling well. She refused to offer excuses.

Her academic journey was remarkable—from Queen Amina College, Kakuri, Kaduna, to Columbia College (Los Angeles), where she earned a B.A. in Mass Communication (Radio & Television), and later a B.A. in Journalism and Mass Communication from City University, London. She obtained an M.A. in Communication Arts (Film) from Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles; a PGD in Development Studies from Mount Carmel Golda Meir Institute, Haifa (Israel); and a Ph.D. in Communication. She remained an epitome of academic excellence, constantly attending national and international courses and conferences.

Her professional career was equally distinguished: Public Relations Officer at the Nigerian Consulate in Atlanta, Georgia (1982–1984); News Editor at NTA Jos during her NYSC (1984–1985); continued at the NTA until 1987; and later joined the ABU Mass Communication Department in 1999, where she rose to become Northern Nigeria’s first female Professor of Broadcasting. Her legacy of scholarship and mentorship shaped generations of communicators.

The news of her demise at the age of 67 came to me as a rude shock. Prof will be forever remembered. We do not mourn as those without hope; rather, we rejoice that she has finished her race and received a crown of glory. We have lost a mentor, a patriot, a beacon of hope, a teachers’ teacher, and a shining light in broadcast journalism—whose influence transcended continents and oceans.

As she is committed to the mother earth today, she emptied herself having given her best and imparted knowledge to thousands and even millions across the world and have thus fulfilled mission.

May she rest eternally in the bosom of the Lord.

* Turaki Hassan is a Journalist and Public Affairs Analyst writes from Abuja .